It’s hard being a visionary. Just ask George W Bush.

It’s hard being a visionary. Just ask George W Bush.

You come up with a brilliant idea that you know will fix the world and what happens? Someone somewhere moans that it doesn’t fit the facts. Where’s the evidence, they demand, to support your plan?

That’s pretty much the position Michael Gove’s in these days. Barely a week goes by without a new reform springing from the Education Secretary’s planet-sized brain. The trouble is, outside his immediate circle, few can see the wisdom of his ingenious ways.

The latest wheeze is to turn A-levels into exams taken at the end of a two year course. There’ll be none of those wimpy modules along the way. And out go AS-levels as stepping-stones to the full qualification.

Mr Gove says the shake-up will drive up standards and better prepare kids for further study But few outside Goveworld agree. Nor was anyone calling for the change.

A knee-jerk “no” from the state school unions was perhaps to be expected. More of a surprise was the stinging criticism of the shake up from the independent (private) sector. A “classic case of fixing something that isn’t broken,” was how the head of one of their representative bodies put it. “Rushed and incoherent,” said another.

The UK’s top universities were equally unimpressed. A spokesman for Cambridge said AS-levels, taken after one year, had been a good indication of a student’s potential. So getting rid of them would “jeopardise over a decade’s progress towards fairer access” to the university.

It was a similar story when the education secretary decided to scrap GCSEs, the exams taken at 16. In their place there’s going to be an “English Baccalaureate” or EBacc. It’ll be built around core subjects which, to the horror of many of Britain’s leading cultural figures, don’t include music and the arts at all.

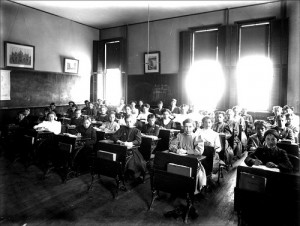

As with his “linear” A-levels intended to get rid of “bite-size learning,” Mr Gove’s EBacc vision is for a “rigorous” (almost certainly tedious) exam system of the type in which he once thrived. Nothing would make him happier than to see silent rows of furrowed-browed youngsters cheerlessly grinding out the facts.

But why? Universities don’t want it and it’s certainly not something businesses are demanding. They’ve been crying out for more vocational qualifications and a greater emphasis on “soft” skills like teamwork and good communications. Test-loving Mr Gove has no time for such touchy-feely nonsense.

Last month, the exams watchdog Ofqual wrote to the Education Secretary expressing its worries over the EBacc. The new exam’s ambitions, its chief said, “may exceed what is realistically achievable.”

Mr Gove took no notice at all. He never does. On this occasion he told the Commons Education Select Committee that he would overrule Ofqual if necessary. “If they still had concerns and I still believe it is right to go ahead then I would do it, and on my head be it.”

Which brings me back to the comparison with President Bush.

In his outstanding 2004 analysis of the Bush administration, Ron Suskind of the New York Times describes a conversation with a Bush aide who had taken exception to Suskind’s journalism:

The aide said that guys like me were ”in what we call the reality-based community,” which he defined as people who ”believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.” I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. ”That’s not the way the world really works anymore,” he continued. ”We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out.”

And that is exactly what Michael Gove is doing. From dishing out free schools to the imposition of academies (about which the jury is still most definitely out) to inventing new exams and extolling the virtues of an educational era in which only the fittest survived, the Education Secretary is indeed creating his own reality.

Unfortunately, as with the Bush administration, it rarely bares any resemblance to the demands and constraints of real life.